Marc Seguin was a precursor of the industrial revolution (suspension bridges, tubular boilers, railways). In contrast to many of his contemporaries, he intervened in numerous fields and disciplines (scientific theory, innovation, astronomy, teaching, etc.). In addition, he practices an approach that is comparable to current creativity processes, including design thinking.

Two factors explain this diversity and this approach. On the one hand, the teenager Marc Seguin will spend three years with his great-uncle Joseph de Montgolfier. This brilliant mind invented (with his brother Etienne) the aerostat and settled in Paris where he was admitted to the Academy of Sciences, taught at Arts et Métiers and was part of the famous lodge of the “nine sisters” where he frequents Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and many other scholars and artists of this revolutionary time. He is also the mentor of young Annoneans sent to Paris to complete their education. He pays particular attention to young Marc whose talents he discerns. He knows that Marc will not be able to continue his studies in Paris for family reasons and gives him a solid scientific foundation based on the principles of the Enlightenment (observation, reason and science) without forgetting his admiration for Newton.

Back in Annonay, Marc Seguin will quickly be identified as an exceptional subject. He completes his scientific and technical training. He created a workshop for experimenting as well as a first astronomical observatory. The richness of the Annonay ecosystem at that time was an ideal environment for developing his curiosity and intuition and allowed him to respond to a wide variety of requests which accustomed him to intervene in many areas. He does this by resorting to observation, imagination, self-training, prototyping and testing, without forgetting to surround yourself with the advice of experienced people. And by paying attention very naturally to the societal needs of his time, small and large, universal or domestic.

It is this approach that he will pursue to undertake projects as innovative and important as the cable suspension bridges (1825), navigation on the Rhône, the tubular boiler (which will equip George Stephenson’s “Rocket”) (1827) or even the construction of the first modern railway line on the European continent (1832), projects which earned him to be considered as a precursor of the industrial revolution in France. But also to tackle societal projects later (social buildings, follow-up care establishments, businesses for retirees), which will just as naturally lead him to be interested in transmission.

In this he is closer of his English and American colleagues (“the civil engineers”). He is an “engineer-entrepreneur” who first considers the world around him and develops a work approach and ad hoc solutions. Its practical approach supported by targeted scientific or technical research that responds to a societal demand or need is close to what we today call design thinking. A working method that becomes an art of life. Very far from the abstract method based on mathematics of the great schools and the great bodies of the State.

This creative approach is inspiring. Observation of uses, sense of enterprise, concern for social utility, use of knowledge and networks to find relevant information, experimentation are on its dashboard. So many themes that resonate with 21st century innovation and so many factors of creativity.

In 1860, at age 75, he did better. He will “embody” his approach to the world and his creative approach in Varagnes: he is no longer an entrepreneur but wants to continue to grasp the scientific and societal issues of the time which interest him, to pursue research, creation and transmission to his as he pleases and do it with the approach that has been his all his life. He created Varagnes for this purpose. A unique approach which creates a unique place.

It will “equip” Varagnes accordingly: journals, books, archives, scientific instruments, artistic equipment, observatory, testing room, mechanics workshop, chemistry workshop , carpentry, blacksmithing and also classroom to transmit. (see the chapter “Learn more about Varagnes”)

His descendants will not be left behind in terms of creativity. One of his sons, Augustin, who inherits Varagnes, increases the spectrum of family curiosity to artistic creation. Augustin was both an engineer, entrepreneur, innovator and artist. Varagnes testifies to his gifts: paintings and sculptures, decoration of the interior of the greenhouse, apse of the chapel etc. He maintained close contact with the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, at the same time as he discussed optics, photography and acoustics with Louis Lumière who came to Varagnes. From 1866 until the end of the century, Augustin directed the Chantiers de la Buire, a conglomerate commensurate with his intellectual curiosity which produced railway carriages, electric turbines, tramways, cars, looms, astronomical telescopes, etc. With Augustin, art intersects with science.

His son Marc will use his studies in photography to develop radiology and equip the Annonay hospital.

Another son , Louis, created the company Gnome, today Safran, and developed with his brother Laurent the rotary aircraft engine, a key innovation in the history of aeronautics. Their brother Tintin filed more than 65 patents and was a distinguished aviator.

One of Augustin’s daughters, Rose, was a talented painter and another son, Joseph, was a very original poet who contributed to introducing Haï Kai in France at the beginning of the 20th century and devoted one of his Haï Kai books to the war of 14-18. One of his grandsons, Raoul de Warren, was a historian and novelist. The artist’s studio preserves numerous testimonies of the works of members of the family.

And the list is not exhaustive!

Some key dates of Seguin innovations and businesses are illustrated below.

Tain-Tournon bridge

1st model of Marc Seguin’s Suspension Bridge

As an architect and inventor, Marc Seguin created suspension bridges following studies into the traction of metal cables in 1822. The first of these was inaugurated on 25/8/1825 between Tain and Tournon.

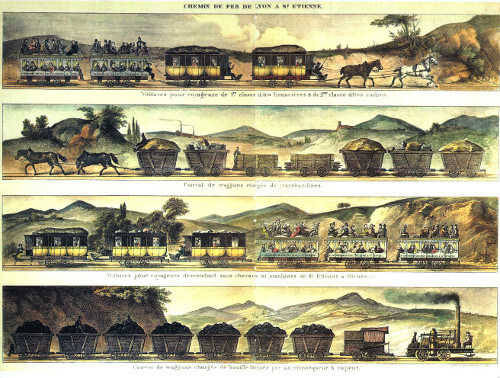

Engraving

Railway from Saint-Etienne to Lyon

In 1826, the Seguin brothers – Marc, Camille, Paul, Charles and Jules – decided to study the creation of a railway line between the Saint-Etienne coalfield and the city of Lyon. They won their tender the same year. In 1833, the entire line was opened.

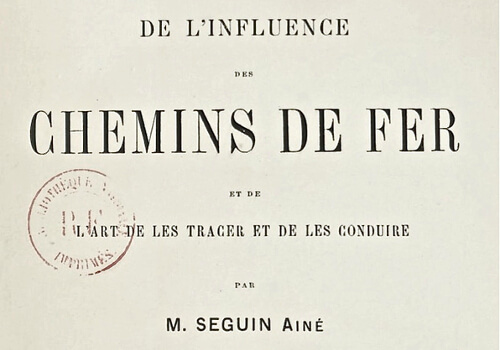

by Marc Seguin aîné

The influence of railways and the art of laying out and operating them

Paris 2012 exhibition

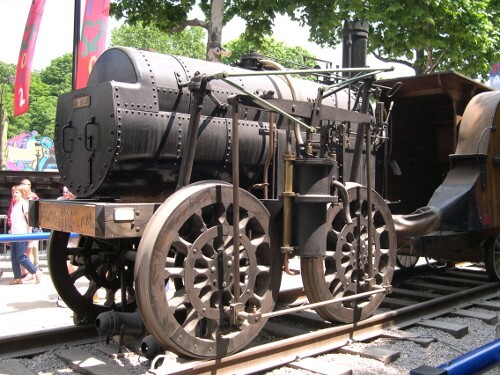

The Seguin Locomotive with Tubular Boiler

Marc Seguin’s locomotive made its first runs in 1829, implementing the principle of the tubular boiler, patented by Marc Seguin in 1827. It was the real trigger for the use of steam as a mechanical power.

Automobile Buire

Founded in 1847, Les chantiers de la Buire is a unique company in Lyon, headed by Augustin Seguin from 1866 until his death in 1904. This steel construction company was highly successful in the production of rolling stock for the railways, but also participated in the development of car manufacturing. It also diversified into special constructions such as weaving looms, electric motors and astronomical telescopes.

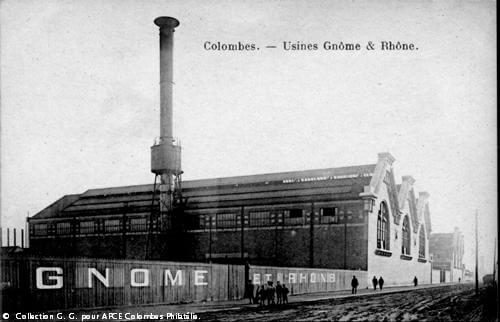

Colombes

The Gnome and Rhone Factory

Louis Seguin opened an industrial engine factory in Gennevilliers in 1895. In 1905, he and his brothers founded Société du moteur Gnôme, targeting the boat and then car engine markets. Under Laurent’s impetus, the company began manufacturing a rotary aircraft engine in 1908. On 12 January 1915, Gnome absorbed Le Rhône to form the “Société des moteurs Gnome et Rhône”, which produced 25,000 engines, plus 75,000 under licence, during the First World War.

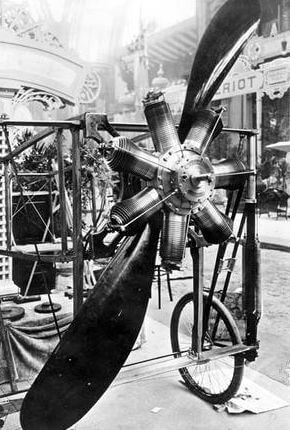

Exhibition at the 1st World Aviation Meeting in Reims (1909)

Gnome Rotary Engine (Omega model)

At the end of 1907, the Seguins began work on the 1st rotary engine specially designed for aviation, and which was to be the best aviation engine for several years.

On theSeguinfamily, see the website www.art-et-histoire.com

On Marc Seguin, see the following books:

M

Many websites are devoted to Marc Seguin, including Wikipedia.

About La Compagnie du chemin de fer de Saint-Étienne à Lyon

See the dedicated Wikipedia page: here

On Louis and Laurent Seguin, see Wikipedia ” Louis Seguin ” ” Moteurs Gnome ” ” Safran”and other sites and articles mentioned there

See also “J’ai vu naitre l’aviation” by Henri Fabre

About Joseph Seguin

“En pleine figure. Haïkus de la guerre 14-18”, anthology compiled by Dominique Chipot, Editions Bruno Doucey, Paris, 2013.

Recording of the biography of Joseph written by Geneviève Besson, his daughter

“En pleine figure. Haïkus de la guerre 14-18”, anthology compiled by Dominique Chipot, Editions Bruno Doucey, Paris, 2013.

About Rose Seguin Bechetoille

Coming soon…

On Raoul de Warren

See the bibliography published by L’Herne

On the Manginis, see Collections de Varagnes (in the chapter “En savoir plus sur Varagnes“) and “Les voies des Mangini , entrepreneurs humanistes lyonnais” by Laurence Duran Jaillard. Libel Lyon. 2018